“Laozi grew increasingly weary of the moral decay of life in his home town in the Chengzhou province. When he was about 80 years old he decided to leave civilization and live as a hermit in the wilderness. As he was leaving through the city gates of his home town a guard recognized him and asked the old master to record his wisdom for the good of the world and for future generations before he left. Laozi sat on the ground next to the guard station and wrote a set of writings (or poems) which we now know of as the “Tao Te Ching”.

Once he completed the writings he handed them to the guard and walked away never to be heard from again.”

The story above is a summary I put together of the various origin stories of the Tao Te Ching. The stories vary in many details. In the stories Laozi lives anywhere between 200 and 700 BC. Laozi spent a few minutes or maybe it was weeks writing down his thoughts. He handed the guard the writings and the guard spread the work to others… or maybe the guard was so inspired by Laozi’s words that he followed Laozi in to the wilderness. If you read 10 accounts of Laozi’s exit from town you will get 10 different versions of the story.

It would be a very American way of thinking to hear this story and wonder if it is a true story. If you were to ask a Taoist Master if this story is true they would probably give you an answer like: “The truth of the story of Master Laozi is in the wisdom and advice you can learn from it. Be like the Master, Be like the Tao.”

If you persisted and said: “yeah, but did it really happen?” The Taoist Master would probably do something like pat you on the head and tell you to return when you are mature enough to hear about The Way.

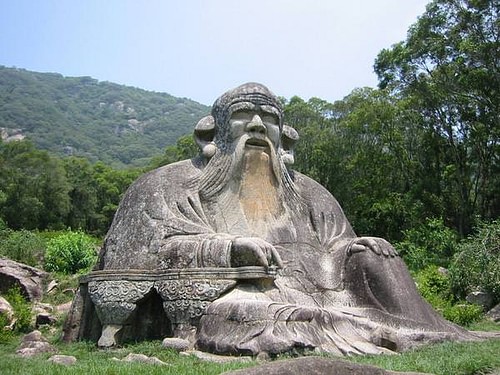

The point of the origin story of Laozi is not whether it happened or not. There is very little evidence that Laozi existed at all. Even the name ‘Laozi’ is just a title that you would give to someone that means something like ‘venerable one’ or ‘wise person’. It is entirely possible that Laozi was real. It is also possible that Laozi was a name given to several people who lived over generations who were the wise people in some location that people respected. It is also possible that Laozi is an entirely fictional character who was added to the Taoist story much later to make for a good origin story.

The points of the story of Laozi is not history. It’s pearls of wisdom like:

- Be like master Laozi and give up all worldly possession and desires to go be one with nature (The Tao)

- Be like master Laozi and offer your wisdom freely to people who ask for it. Seeking payment for wisdom takes you away from The Tao

- Be like master Laozi and don’t let worldly problems distract you from The Tao

In our first episode we talked about Jamesian thinking. Jamesian thinking is a deeply analytical philosophy that encourages you to fully engage with what can be known. If there is data you should study it deeply. If there is no evidence of a thing then you should cast it aside. Jamesian thinking is about a desire for understanding that can only be reached through real-world practical details.

Taoism asks you to do something very different. Ignore all that you can see; trust only what can be discovered by turning inward. Through clearing your mind of problems you can reach truths that the day-to-day world get in the way of you seeing. Like Jamesian thinking it is about exploring ideas deeply. Taoism wants you to be thoughtful. The inputs of these two ideas are very different but the exercise of trying to understand the world deeply is similar.

If you know Taoism at all it’s because the sayings have a sing-songy ironic quality to them. The writings are full lines like: “Do by not doing” or “the path to where you are going is to stay where you are” and so on.

When Taoism says to ‘do by not doing’ it does not mean to lie down somewhere and wait for the world to come to you. It means something more like: If you are living life through the Tao and are in harmony with the universe then the things you do will feel easy because they are the things you are supposed to be doing.

Taoism has practical advice as well. Taoism isn’t just philosophy and Yoda-style words of wisdom. For example a great bookend to the story of how the Tao Te Ching was written is the story of the Wheelwright:

QUOTE:

Wheelwright: May I ask what words my lord is reading?

Duke: I am reading the words of a wise sage.

Wheelwright: Is this wise sage still alive?

Duke: No, no. He’s been dead for centuries.

Wheelwright: In that case my lord is reading the dregs of the men of old.

Duke: What business is it of a wheelwright to criticize what I read? Explain yourself!

Wheelwright: Speaking for myself, I see it in terms of my own work. If I chip at a wheel too slowly, the chisel slides and does not grip; if too fast, it jams and catches in the wood. Not too slow, not too fast; I feel it in the hand and respond from the heart, the mouth cannot put it into words, there is a knack in it somewhere which I cannot convey to my son and which my son cannot learn from me. That is how through my seventy years I have grown old and yet I am still chipping at wheels. The men of old and their un-transmittable messages are dead; and what my lord is reading is the dregs of those dead men, isn’t it?

End Quote: The Wheelwright, by Master Zhuang

We started with the story of Laozi. That story places all of the importance of Laozi’s existence on the writings he leaves behind. But the Wheelwright, as part of the same Taoist ideology, admonishes you for doing nothing but reading the pages of words written by the long dead. Laozi’s words, by themselves, are the dregs of dead men.

The point of the Wheelwright story is that life is a skill. You cannot learn a skill like making wooden wheels, or playing the piano, or living a quality life simply by reading a book. You have to do it. The only way to master life, as a skill, is to live it and learn well the lessons it has to teach you.

Taoist thinking encourages an active mind. It encourages you to engage deeply in things. But it also advises that being distracted by worldly things only serves to take you away from The Tao (The Way). Endlessly debating what is real and what is not is a pointless game. Better to focus on what can be learned by striving for harmony and then living life on that harmonious path. How do you get on the right path? A righteous life comes in many forms. Should you live as a hermit in the woods or be a wheelwright? The answer is that you should focus on getting in touch with the Tao and then follow it where it takes you. Do by not doing.

Additional Reading #1: The World’s Religions…, by Huston Smith

In 1958 Huston Smith wrote a book about the Religions of the World. This book began with a chapter on Hinduism. In that chapter on Hinduism Smith begins in the New Mexico desert at a nuclear bomb test. He quickly takes you to the Hindu text, the Bhagaavad-Gita, and to the quote “I am become death, the shatterer of worlds…”

With the success of the new movie Oppenheimer this quote, and Oppenheimer’s use of it, have come back in to view in American society. But the quote and Oppenheimer were well known long before Christopher Nolan presented them in his movie.

Hustom Smith used this Oppenheimer moment to kick off his book by connecting the reader to Hinduism through Oppenheimer. I’m not sure what percentage of Americans from 1958 to now first heard this quote from Hinduism from Oppenheimer or from Smith’s book. But the overlap should not be ignored. Smith’s book is a major influencer on how most Americans see world religions.

Smith’s book has been read by millions of Americans over the past 70 years. If you are over 60 years old and have a book shelf in your house you probably have a copy of Smith’s book on that shelf. Smith was friends with people like Timothy Leary (LSD pioneer) and other leaders of the hippie movement. As such Smith’s work became a must-read for 60’s and 70’s college kids and counter-culture types. One of the books’ biggest influences was the chapter on Taoism. This book led millions of young Americans to be curious about ‘Eastern Religions’ and what those could offer as alternatives to standard western Christianity.

In the years since Smith’s book, Taoist ideas have become fully infused in to “foo-foo” American culture. Go in to a store that sells incense and healing crystals and you are sure to find dozens of books with variations on Taoist writings. A Taoist parable for each day of the year. Taoist horoscopes. The Tao of Pooh and the Te of Piglet. It’s a major part of that counter-culture scene to this day.

I chose Taoism to talk about in this chapter on abstract spiritual thinking because the Tao Te ching is one of my favorite books. I come back to it often and always find it mentally calming. I could have chosen several other religions like Hinduism or Buddhism to present this type of religious behavior but those religions never spoke to me the way The Tao does. That said, if you are someone who wants to understand other religions then Huston Smith’s Religions of the World book is easily the best place to start. I listed it as 1958 but he did an updated release in the 1990’s so there is a more current version that presents global religion in a fair and interesting way if you are curious about that sort of thing.

My favorite parable goes something like this:

“When the Master governs, the people are hardly aware that he exists.

- The next best type of leader is one who is loved. But under the beloved leader the people become like children. They idle under their beloved leader, waiting for him to resolve everything.

- Next is a leader who is feared. The people don’t move and bitterness and unproductivity rule the kingdom.

- The worst leader is one who is despised. For their people will eventually rise up to destroy them. If you don’t trust the people, you make the people untrustworthy.

- The best leaders are the ones who don’t talk, they act. Under this type of leader, when the work is done, the people say, “We did this ourselves!”

Additional Reading #2: Laozi’s Dao De Jing, by Ken Liu and read by BD Wong

I have read many versions of the Tao Te Ching. Easily the best I’ve ever come across is the audio-only version by Ken Liu. It is read by the amazing actor BD Wong and includes musical accompaniments. The entire audio book is about 3 hours long.

The structure of the work includes other Taoist texts beyond the Tao Te Ching and also includes commentary on the work by Liu. It presents Taoist writing in a way that allows you to engage in a meditative way and really experience the words of these great works from Taoist tradition.

I borrowed the origin story of Laozi and the Wheelwright story from Liu’s work. Liu has a lot to offer on those stories that I didn’t cover and so if you found any of this interesting then Liu’s book will surely be a hit with you.

A final comment on this work: BD Wong is an amazing actor and it’s worth mentioning that his contribution should not go unnoticed. It is a real treat to have an actor of his stature contributing his voice to the Taoist works. If you like audio-books then Wong’s work here alone is reason enough to listen to this.

Leave a comment